Logistical turbulence: Between valorization and violence along the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/02637758241243163

A research team at the University of Vienna

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/02637758241243163

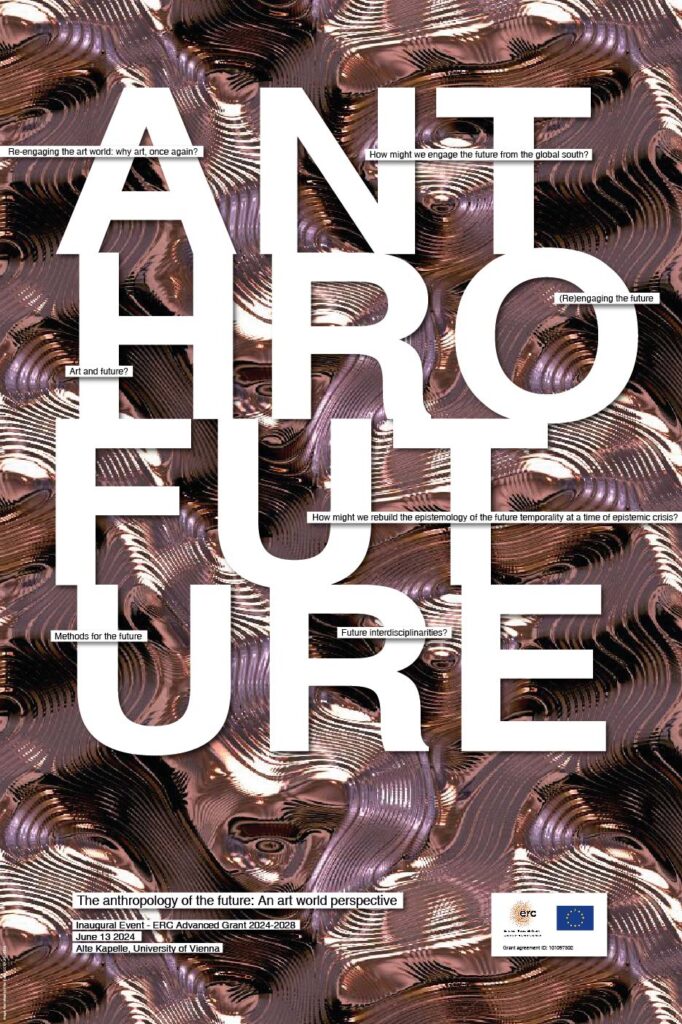

Two PhD positions are currently available at the Institute of Cultural and Social Anthropology at the University of Vienna in the ERC project “‘The anthropology of the future: an art world perspective’ (ANTHROFUTURE)” (PI: Manuela Ciotti).

The extended application deadline is 16.06.2024

Two PhD positions are currently available at the Institute of Cultural and Social Anthropology at the University of Vienna in the ERC project “‘The anthropology of the future: an art world perspective’ (ANTHROFUTURE)” (PI: Manuela Ciotti).

The application deadline is 26.05.2024

Manuela’s ERC project ‘The anthropology of the future: an art world perspective (ANTHROFUTURE) started on the 1st of January 2024

I recently reconnected with a series of photos I took from my rooftop in Dakar, Senegal. Month by month, at the syncopated pace of construction, the view of the infamous and holy island of Yoff was obstructed. Block by block, walls and floors were erected. The wind found new obstacles on its way to cool down streets. The concrete jungle was growing, accompanied by the rhythms of builders’ sweaty choreography. The skyline is transforming, and the horizon becoming an urban luxury.

2023. ‘Why do you fall in love? Why do you worship Vishnu and Shiva?’Decolonising Collecting through the Visual-Material Cosmos of a Nation’s ‘Interior Designers’. Third Text, 181 (2), 262-284

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09528822.2023.2251855

Ciotti Manuela 2023. Make no mystique! Collectables’(dis)appearances in a transoceanic perspective. Third Text 181

A private museum originally from Sweden just opened a branch in Berlin. It is housed in a landmark former art squat, a memory of an era whose destruction sent ripples across the Berlin community (read more here) , and stands in contrast to the myriad community-ran alternative art spaces across the city. Here in the photo, an advertisement for the museum posted at Kottbusser Tor, at the heart of Berlin’s working class and migration trajectories, in the proximity of an established community museum and numerous BIPOC-owned art and culture spaces.

Pierre is currently on fieldwork in Dakar, in the midst of the rainy season. The ambient air is hot and humid, and sporadic flooding can make daily life challenging. Fresher air is giving some rest only early in the morning. This soothing moment offers beautiful sunrises playing with clouds and birds’ songs coming from secret nests hidden in concrete walls. Time stops before the hectic day starts.

We wish you a good and fulfilling new academic year!